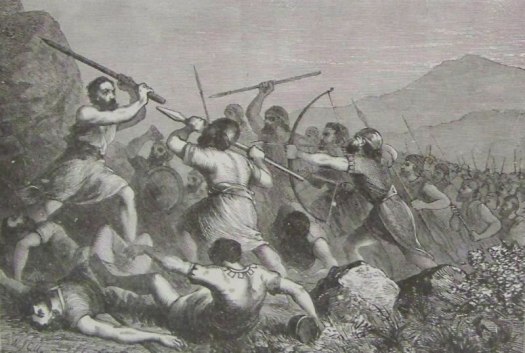

Featured image: Battle between the Scythians and the Slavs ( Wikimedia Commons ).

The Scythians may not be the original inventors of asymmetrical warfare, but one could argue that they perfected it. Before and during the Scythian arrival, many nations fought by conventional methods. In other words, the established civilizations of Assyria, Babylonia, and Persia, used taxes to feed, equip, and maintain their large armies. Overall, one can see the massive expense it is to arm and defend a nation when war comes a-knocking. Lives and money are lost, doubly so if you go on the offensive at the expense of your nation’s pocket.

The Scythians, on the other hand, needed none of these, for they were tribal based and seemed to come together only in a time of war. Thus, most issues did not hinder them, such as the laws of supply and demand in the military-economic sense, which would affect an established kingdom or empire. The land was their supplier and demand was when they were in need of resources. For Scythians to sustain life, they had to move to new regions in search of ample pastures suited for their horses to graze and abundant with game, while the land they moved from was left to rest. But one has to be cautious as well, for even though the Scythians moved around, many stayed within their tribal territory. In some cases, they ventured into another tribal territory due to the need to sustain life for both tribe and livestock.

Scythian Horseman depicted on felt artifact, circa 300 BC. Public Domain

When one examines the Scythian lifestyle, one can easily gain an understanding of the type of warfare necessarily carried on against more sedentary (non-migratory) people, like those in Mesopotamia. The Scythian took a guerilla approach to warfare as their method, not to be confused with terrorism. The term guerrilla warfare means irregular warfare and its doctrine advocates for the use of small bands to conduct military operations. Herodotus mentions their method of warfare when King Darius of Persia campaigned against them:

“It is thus with me, Persian: I have never fled for fear of any man, nor do I now flee from you; this that I have done is no new thing or other than my practice in peace. But as to the reason why I do not straightway fight with you, this too I will tell you. For we Scythians have no towns or planted lands, that we might meet you the sooner in battle, fearing lest the one be taken or the other wasted. But if nothing will serve you but fighting straightway, we have the graves of our fathers; come, find these and essay to destroy them; then shall you know whether we will fight you for those graves or no. Till then we will not join battle unless we think it good.”

The description indicates that the Scythians against whom Darius is warring have no center of gravity; more on this later.

Swarming

The Scythians are best known for swarming the enemy, like at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE, where they demonstrated this tactic during the initial stages of the attack. The swarming tactic is the first stage before any other mechanism is executed, like feinting or defense in depth.

To summarize, the definition of swarming would be a battle involving several or more units pouncing on an intended target simultaneously. The whole premise of swarming in guerrilla warfare, as indicated in the U.S. Army Field Manual (FM) 90-8 on the topic of counterguerrilla operations, is to locate, fix, and engage the enemy, but to avoid larger forces unless you possess units capable of countering the other. This would allow other units to take advantage of the enemy, which is rare in most battles involving the Scythians. The key principle of swarming is that it does not matter if you win the battle so long as you do not lose the war. It is designed to disorient the enemy troops.

The swarming tactic comprises many units converging on the intended target; however, the swarm moves with the target in order to fracture it. Thus, the method of swarming is to dislodge the enemy piecemeal, causing rank and file to implode. This is due to longstanding, snail-like movement during battle, meantime being continuously pelted from afar by projectiles; fear takes over, demoralizing an army. Roman soldiers were to have a taste of this, for they had a space of three feet all around them to allow for movement and maneuvering in battle. The Scythians took advantage of their three feet, as Plutarch mentions, at the battle of Carrhae: “Huddled together in a narrow space and getting into each other’s way, they were shot down by arrows.”

The heavy barrage of arrows would cause some to wander off, bit-by-bit, thus allowing horse archers to concentrate fully on the wandering enemy. In this scenario, one can argue that the initial battle tactic is to pelt the enemy with a volley of arrows, keeping the target tight in order to fracture it, which allows the horse archers to go from random pelting to accurately killing the enemy. In other words, they switch from firing up into the air to firing forward at the enemy, as demonstrated at Carrhae in 53 BCE.

Scythians shooting with the Scythian bow, Kerch (ancient Panticapeum), Crimea, 4th century BC. (CC BY-SA 3.0 )

Now, before we go any further, let me briefly make the case that swarming has many different methods or tactics, but the Scythian swarm is not like that of others. However, a swarm is a swarm, but the method varies. Case in point, “mass swarming” is the most sought- after method in both the ancient and medieval world, demonstrated by massive conventional armies that would eventually separate or disassemble and perform convergent attacks over a region or province from its initial phase. The “dispersed swarm” is the preferred tactic in guerrilla warfare, where the body separates and converges on the battlefield without forming a single body.

The whole premise of swarming in guerilla warfare is to engage quickly but to avoid larger forces. Pharnuches, one of Alexander’s generals, made the fatal mistake by falling for the Scythian feinting tactic, in which he chased after the Scythians, only to find himself ambushed and swarmed. Pharnuches should have never been given command, because he was a diplomat, not an experienced officer.

Mosaic detailing the famous military leader and conqueror Alexander the Great/Alexander III of Macedon. Public Domain

The Battle of Jaxartes is a fine example of the swarming tactic, but rather small in scale. The Scythians harassing the forces of Alexander did not appear to be a large force. Rather, the Scythians at the battle intended to demoralize the enemy, and if that did not work, they could always lead the enemy farther inland and begin the strategy of defense in depth. Alexander knew better after he defeated the Scythians at Jaxartes in 329 BCE. Alexander understood quite well that if he were to pursue the Scythians further inland, his forces would be open to hit and run attacks, famine, and psychological attrition, none of which is desirable. Even Alexander understood the limits of empire, especially when his worldview did not incorporate the lands to the north.

The Battle of Jaxartes was a loss for the Scythians and a victory for the Macedonians. However, two important demonstrations of the tactics are visible at the battle. The first tactic is swarming, the second is what I like to call the swarm-anti-swarm tactic developed by Alexander, commonly referred to as “anti-swarming.” In fact, Alexander had to swarm in order to achieve victory. The swarm-anti-swarm counters the enemy with a bait-unit. Once the enemy converged from several sides, the remainder of the forces would converge on the area and swarm the enemy. Alexander learned quickly to adopt this tactic of closing in on the enemy and attacking from all directions for future use.

By Cam Rea

References

Ian Morris, Why the West rules–for Now: the Patterns of History, and What They Reveal About the Future (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010), 277-279.

Herodotus, The Histories, 4. 127.

Sean J.A. Edwards, Swarming on the Battlefield: Past, Present, and Future, (Santa Monica: Rand Corporation, 2000), xii.

U.S. Department of Defense, Counterguerrilla Operations, (Washington DC: Department of the Army, FM 90-8, August 1986), Chapter 4, Section III. 4-10.

Polybius. 18.30.6

Plutarch, Crassus, 25.5

Kaveh Farrokh, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War (Oxford: Osprey, 2007), 133.

John Frederick Charles Fuller, The Generalship of Alexander the Great, (New York and Washington D.C.: Da Capo Press, 2004), 118-120.