General Publius Ventidius is probably one of the most overlooked if not completely forgotten, generals in military history. Maybe it is because Ventidius grew up poor like most Romans… Or perhaps it was due to the reports that he sold mules and wagons before joining the Roman army.

Despite this, Ventidius would have a distinguished military career, accompanying Julius Caesar during his campaign against Gaul and partaking in the Roman Civil War. Then in 45 BCE, Ventidius took up Caesar’s offer and accepted the post of plebeian tribune when the senate was reorganized and expanded.

Finally, on top of everything else, it may have been this forgotten general, with whom we concern ourselves today, who was responsible for reversing the Parthian tide and changing the course of Roman History.

We will now look at the series of battles to amend the marginal position in the history books designated to poor Ventidus.

It was in 39 BCE that Mark Antony assigned Ventidius Bassus the mission to retake Asia Minor. Reports had reached Antony while he was in Greece that the Parthians had finished their campaign in Asia Minor for the year. These intelligence reports most likely came from the province of Asia, which was, at the time, loyal to Rome. From this news, Antony was able to draw up his plans.

He probably knew that most of the Parthian army would retire for the winter and return home to their respected nobles. This would mean that those who remained were local militias with questionable loyalty to garrison the cities throughout Asia Minor. In addition, Antony understood the need to attack now to inhibit any further Parthian progress coming next spring.

Antony saw this as a perfect opportunity to surprise the enemy.

And so, once the coast was clear, Antony took a chance and placed a few legions under the command of our dear Ventidius, who subsequently set sail for the province of Asia. Vantidius’ mission was simple: establish a beachhead in the province of Asia and push inland.

Battle of the Cilician Gates

Ventidius’ landing was unexpected. This only shows the lack of intelligence gathering on the part of Labienus, head of the Roman-Parthian army. Once the Roman forces were accounted for, Ventidius began pushing eastward in a ‘search and destroy’ mission.

Word spread rapidly that the Romans had arrived. When the message reached Labienus, he was startled and terrified, for he “was without his Parthians.” The only troops available to him were the neighborhood militia.

Labienus quickly fled the province of Asia and headed east, seeking military support from his co-ruler, Pacorus, a Parthian prince and son of King Orodes II.

Meanwhile, Mark Antony’s man, Ventidius, took his own chance and abandoned his heavy troops. He pursued Labienus with his lightest forces.

Eventually, Ventidius caught up with Labienus and cornered him near the Taurus range. He chose the high ground to look down upon Labienus’ encampment. But there was another, more important, reason why Ventidius took the high ground; he feared the Parthian archers.

It was a standoff as both generals encamped for several days, waiting for the arrival of their main forces. As the bulk of the armies finally arrived, the Romans and the Parthians hunkered down for the night.

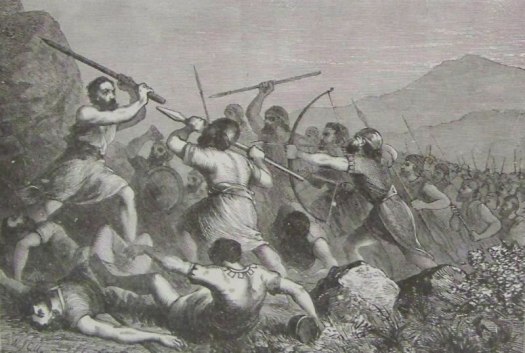

At daybreak, the Parthians, over-confident with their numbers and past victories, decided to start the battle before joining forces with Labienus. Unfortunately, these were not the famous and deadly Parthian horse archers… but the heavy cavalry, or cataphract. Once they were at the length of the slope, the Romans charged down on top of them and repelled the enemy with ease, for the Romans had momentum.

While the Romans inflicted significant casualties, the cataphracts caused even more harm to themselves in the chaos.

The cataphracts were at the top of the slope, where all the fighting took place, but when they retreated, they ran into their men coming up the hill. Instead of descending to rally around Labienus, they bypassed their general and headed straight for Cilicia. It was absolute chaos.

Ventidius, seeing that the Parthians were scattering and fleeing, decided to bring his men down from the hill and march on Labienus’ camp.

Both armies were now face to face… But Ventidius decided to stay put.

Why would Ventidius do this? Well, he was informed by deserters that Labienus was going to flee the camp come nightfall. Therefore, Ventidius decided it was better to set up ambushes rather than have an all-out pitch battle, which would result in losing many men and resources during the process.

Once nightfall came, the ambushes set in place worked as planned, killing and capturing many… that is, except for Labienus. Labienus was able to escape by changing clothes… His destination was Cilicia.

However, Labienus was not able to hide for long. Demetrius, a former slave and then “freedman,” turned bounty hunter and arrested him. He was quickly executed after Demetrius turned Labienus over to the Roman authorities.

Battle of Amanus Pass

With Labienus dead, Ventidius was able to secure the province of Cilicia. This did not mean they won; the mission was far from finished. To complete it, Ventidius devised a plan to trick the Parthians.

Ventidius sent a cavalry, headed by the officer Pompaedius Silo, to scout out the Amanus Pass, a strategic mountain path connecting the province of Cilicia and Syria. Not far behind Silo would be Ventidius, along with a small contingent of troops to aid in the fight.

Meanwhile, on the Parthian side, Pacorus understood that the Romans would march through and invade Syria if the same Amanus pass were not secured. Therefore, he felt the best method was to station a garrison there to bottle up the small mountain road.

So Pacorus stationed Pharnapates, a Parthian lieutenant considered the most capable general of Orodes, to wait for the Romans to come. Once Silo reached the pass, the two sides engaged in battle immediately.

But don’t forget – this was, in fact, an elaborate trick. Silo’s real mission was to lure the Parthians away from their strongest defensive position. In doing so, Ventidius would either attack at the flank or from the rear.

The Romans were giving the Parthians a taste of their medicine by using the same tactic that worked so well against them at the Battle of Carrhae. With many of Pharnapates’ cataphract lured away, Ventidius fell upon the Parthians unexpectedly. Pharnapates, along with many of his men, perished during the engagement.

With the Amanus Pass now clear, the invasion of Syria was imminent.

With the Amanus Pass secured, Ventidius, head of the Roman forces, pushed south into Syria. Pacorus, the Parthian prince and co-leader of the Roman-Parthian army, was done fighting… at least for now.

He abandoned the province to the Romans in late 39 BCE. With the Parthians out of the way, Ventidius led his forces to the province of Judea.

Ventidius’ mission in Judea was simple and lucrative: to rid the province of any remaining Parthians. He was also there to remove the anti-Roman King, Antigonus, and to restore Herod to the throne.

But Ventidius did neither.

Instead, he bypassed Herod’s royal family, besieged by the Antigonus troops on the top of Masada, and went straight for Jerusalem. Ventidius played psychological warfare with Antigonus, making him think he would take Jerusalem.

This, however, was just another ruse.

Ventidius promised not to attack Jerusalem… that is, unless he received vast wealth from the king. In his mind, Antigonus had no choice but to capitulate to Ventidius’ demands.

Make no mistake, Ventidius would still support Herod and place him on the throne. But while Herod was still far away and his brother besieged, Ventidius thought he might as well make some money while they waited.

After filling Ventidius’ coffers, he took the bulk of his forces. He headed back for Syria, leaving his second, officer Pompaedius Silo, in charge to deal with the ‘Jewish problem’.

The Ruse

However, King Antigonus would come up with a ploy of his own; he bribed Silo multiple times. Antigonus hoped to buy time so that the Parthians could assist while he kept the Romans at bay.

Unfortunately for King Antigonus, this would not happen.

When Ventidius returned to Syria, he sent the bulk of his forces beyond the Taurus Mountains to Cappadocia for winter quarters. During this time, the Parthian Prince, Pacorus, planned another invasion of Syria and began to mobilize a substantial number of cavalry from the nearby provinces.

Word of Pacorus’ intentions soon spread, reaching the ears of loyal Roman informants, who then relayed the information to Ventidius. Not only was this information crucial for preparation, it also informed Ventidius that a Syrian noble named Channaeus (also called Pharnaeus), who pretended to be a Roman ally, was, in fact, a spy and Parthian loyalist.

Ventidius likely invited Channaeus over for dinner. During their meeting, Ventidius made it clear that he feared the Parthian would abandon their normal route, “where they customarily crossed the Euphrates near the city of Zeugma.”

Ventidius acted concerned over the issue, making it clear that if Pacorus were to invade Syria much further to the south, he would have the advantage over the Romans for it “was plain and convenient for the enemy.”

Like the good spy he was, Channaeus returned to his home after the meeting and quickly sent messengers to inform Pacorus of Ventidius’ fears.

Come early spring 38 BCE, Pacorus, unwilling to let go of Syria, led his forces south along the Euphrates River based on Ventidius’ supposed fears of engaging the enemy on a plain.

Once they came to the point of crossing, Pacorus realized that they needed to construct a bridge due to the banks being widely separated. It took many men and materials, and the bridge was completed only after forty days.

This is exactly what Ventidius wanted. Ventidius’ disinformation bought him much-needed time, allowing his legions to assemble.

Once the Parthian forces were in Syrian territory, Pacorus likely expected an immediate attack during the bridge construction or the crossing, but neither materialized. With no sign of the enemy, Pacorus became overconfident and began to believe that the Romans were weak and cowardly. Eventually, however, Pacorus found Ventidius at the acropolis of Gindarus in the province of Cyrrhestica.

Ventidius had been at Gindarus for three days preparing his defenses when Pacorus showed up.

Repeated Mistakes

One would have thought that perhaps Pacorus carefully prepared a plan of action in such a situation…. but no. Instead, Pacorus and his officers tossed out the combined arms strategy of utilizing heavy cavalry and horse archers in unison. This had worked many times, so they thought they could take the high ground with little trouble.

Moreover, the arrogant and overconfident Pacorus and his nobles did not want the commoners and horse archers to steal the show, as they did at Carrhae. So they decided to sally up the slope, as they did at the battle of the Cilician Gates.

Once the cataphracts were within five hundred paces of the Romans, Ventidius took advantage of their elitism and rushed his soldiers to the brim and over until both armies met at close quarters on the slope.

Ventidius’ strategy here was simple: by engaging the elite Parthian cavalry, he had cover from the infamous Parthian horse archers.

The Parthians would have learned from previous experiences what not to do. The result of their knee-jerk reaction was devastating. As the Parthian cataphract advanced up the slope, they were quickly repelled back… straight into those still coming up, inflicting great suffering to rider and mount.

This is not to mention those who did make it to the brim were met and repulsed by heavy infantry. And if the heavy infantry did not get them, the slingers would.

These slingers were likely on the left and right side of the Roman infantry, giving them a deadly arc of crossfire. This could be why we do not hear of the Parthian horse archers partaking in the engagement since any attempt to rush towards the front would put them in grave danger.

Even though the Parthian cataphracts put up a stiff fight at the foot of the hill, it was not enough.

The Roman infantry likely swarmed the cataphracts, forcing them into hand-to-hand combat. With the famous Parthian horse, archers neutralized from the fight due to the slingers, and nothing could be done to rescue the situation.

In the ensuing chaos, Pacorus likely tried to make one last push. He, along with some of his men, attempted to take Ventidius’ defenseless camp, only to be met by Roman reserves, in which he inevitably lost his life during the melee.

As news spread that Prince Pacorus lay dead, a scramble to recover his body was attempted. While those trying to retrieve his corpse met the same fate, most of Pacorus’ army quickly retreated. Some attempted to re-cross the bridge that was constructed over the Euphrates but were caught by the Romans and put to death. Meanwhile, others fled to King Antiochus of Commagene for safety.

Victorious Aftermath

This victory shocked Syria. To make sure the Syrians would never rebel against Rome, Ventidius took Pacorus’ corpse, severed the head, and ordered that it be sent throughout all the different cities of Syria.

It was a gruesome sight to behold, but the effect it had on the natives was anything other than negative. Instead, “they felt unusual affection for Pacorus on account of his justice and mildness, an affection as great as they had felt for the best kings that had ever ruled them.”

As for the Parthians who sought refuge in Commagene, Ventidius came after them.

Truth be told, Ventidius could care less about the Parthian refugees. Instead, he was more concerned with how much money he could confiscate from King Antiochus by besieging Samosata, the capital of Commagene, in the summer of 38 BCE.

Antiochus offered Ventidius a thousand talents if he would just get up and go, but Ventidius refused and proposed that Antiochus send his offer to Antony.

Once Antony got word of the situation, he quickly returned to the action scene.

Ventidius was about to make peace and take the lucrative offer when Antony barred him from making such a deal. Instead, Antony removed him from his command and took over the operations from there.

Why? Well, Antony was jealous of Ventidius and wanted in on the glory.

Instead of achieving the desired fame, Antony inherits a protracted siege that goes nowhere and hurts him in the end. When Antiochus offered peace again, Antony had little choice but to accept the now lowered offer of three hundred talents.

After the extortion of Commagene, Antony ventured into Syria to take care of domestic issues before returning to Athens.

As for Ventidius, he went back to Rome, where he received honors and a triumph, for “he was the first of the Romans to celebrate a triumph over the Parthians.”

The Next Generation

As Ventidius celebrated his triumph in Rome, Antony seethed in Athens.

Meanwhile, across the Euphrates in Parthia, King Orodes was grieving over losing his son and army. After several days, Orodes lost the will to speak and eat and began to talk to Pacorus as if he were alive.

It was also during this time that the many wives of Orodes began to make bids as to why Orodes should choose their son for next in line to the throne. Each mother understood that there was this nasty habit in Parthia… once a new king was elected, he would go out of his way to murder his brothers to secure the safety of his reign.

Orodes eventually chose and settled on his son Phraates to succeed him. Soon after Phraates was chosen heir to the throne, he began plotting against his father, Orodes.

Phraates’ first attempt at murdering his father was with a poison called aconite. This failed due to Orodes suffering from a disease called dropsy (edema), which absorbed the poison and had little effect. Therefore, Phraates took a much easier route and strangled his father to death. To make sure his throne was safe, he murdered his thirty brothers and any of the nobility that detested him or questioned his motives for his acts of cruelty. Phraates was here to stay.

But while Phraates went on a vicious campaign to secure his throne, Mark Antony, jealous of Ventidius’s success against Parthia, was prepping and planning an invasion of his own.

Antony’s turn was now to avenge Crassus to fulfill Caesar’s dream.

By Cam Rea

Reference

Like this:

Like Loading...